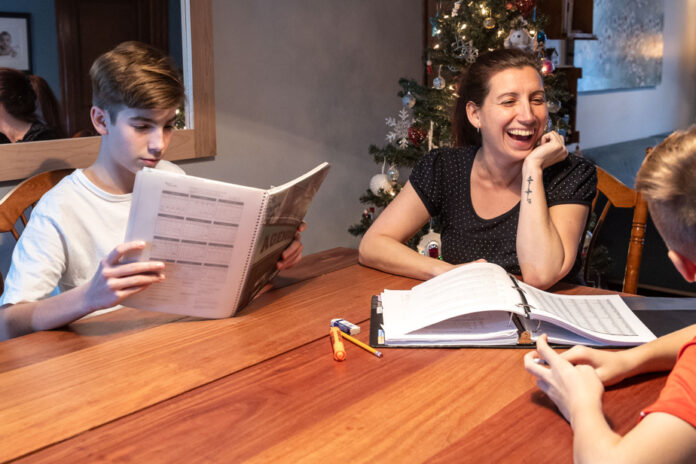

Like many parents, Rachel Blanchard found herself working full-time with her two children when the indefinite general strike of the Autonomous Education Federation (FAE) began. She unreservedly supports teachers, but like many parents, she has one emotion: worry.

“What bothers me the most is the principle of two speeds: those who pay for private school, they get an education, and the others… they fail. It’s unfair,” says Rachel, who points out that this generation of children has already suffered the closures linked to the pandemic.

Her youngest is in the fifth year of primary school (“a big year”), and her oldest is in the first year of secondary school, a pivotal period.

“My eldest and I took the opportunity to do an English homework assignment. We also study verbs, in French and English,” says Rachel, but the latter has nothing else at her disposal: the notebooks remained at school. So his children read, go play outside…

A massage therapist, she has parents among her clients, and many share her concerns, she says. “What are we doing to ensure our children don’t fall behind? »

Parents did even more: at the beginning of December, media reported that tutoring companies saw their clientele skyrocket… which certainly did not reassure the many parents who did not have them done homework or lessons.

Julie Gascon and her partner are more in “survival” mode, between their role as parents, their respective jobs and the picket lines. “It’s difficult to maintain a homework routine,” she confides. My son often says that he is bored of school and that he is not learning anything at the moment, even though we try our best. »

The approximately 368,000 students in FAE-affiliated schools have missed 19 days of school since the strikes began, or 10% of the school year. This is considerable.

“It’s serious, what’s happening, and it’s more serious for some students than for others,” says Égide Royer, psychologist and academic success specialist.

Associate professor at the Faculty of Education at the University of Montreal, Mélanie Paré is also concerned about the impact this closure could leave on students who have greater needs. But for the average student, whose parents are present, the effect will be less, she says. “The majority of children are very resilient; They will quickly adapt to returning to class,” she predicts.

The month of December – the one that was lost – is not the busiest in terms of learning, recalls Mélanie Paré. When they return, teachers will adapt and prioritize essential knowledge. “And they will take into account the fact that many children will not have touched school subjects during the strike,” says the professor.

Is it up to the parents to compensate? The two researchers to whom La Presse spoke agree: teaching the subject is not something that is expected. “In fact, confesses Mélanie Paré, teachers don’t really like it when parents take charge of new learning, because it creates double learning which can harm the work of teachers. »

Égide Royer does not throw stones at parents who have offered a tutor to their children, obviously, but according to him, it will be up to the school to offer hours of tutoring to children who need it, and to give all the support necessary for older students who want to drop out at the end of this long work conflict.

What parents can do, during these weeks of downtime, is to offer their children a form of routine, according to Professor Mélanie Paré. A bedtime, a wake-up time, family meals, and activities away from screens. Like playing outside… and setting aside time to read every day, in order to limit the loss of what you have learned. In particular, we can revise the multiplication tables, she indicates.

Égide Royer believes that children can also take advantage of this period to do new things. Rachel Blanchard’s eldest son, for example, began babysitting for two little neighbors. “It makes him responsible and I’m proud of him,” the mother said.

It’s unavoidable: many young people have spent more time than usual in front of screens to help their parents balance their responsibilities. Rachel Blanchard’s sons are no exception. “It’s not what I want,” she confides.

Neither Égide Royer nor Mélanie Paré take offense. Children can also make positive uses of screens, such as communicating with friends and – why not – listening to a show in English. “The 11-year-old who has his nose in his phone waiting for someone to send him a photo of a cat… he should get through it,” summarizes Égide Royer. People are doing what they can, and I’m not going to ask them to step up like they have a four-year bachelor’s degree in education. »